In 1913, Henry Ford’s moving assembly line transformed carmaking. Ford’s groundbreaking innovation drastically reduced the time it took to assemble a car, enabling mass production and slashing vehicle prices.

More than a century later, carmaking is undergoing a similarly seismic shift. Only this time, Ford Motor Company (F) is scrambling to catch up, rather than leading the charge.

Electric vehicles represent a fundamental shift in the technologies and manufacturing processes that have turned Ford and rivals such as Toyota (TM) and Volkswagen into the biggest car companies on the planet.

Established automakers have been racing to adapt at an enormous financial cost, but are still miles behind Tesla (TSLA) and a crop of new Chinese competitors, including BYD and Xpeng (XPEV).

The world needs affordable EVs more than ever as electric cars will play a big role in hcelping countries cut planet-heating pollution. But can automakers in Europe and the United States — where governments are already planning to ban or limit the sale of new gas and diesel cars — deliver them?

“Ultimately, some of these car companies that have been the cornerstone of how we’ve thought about cars for the last 100 years will be a fraction of their size in future,” said Gene Munster, a managing partner at Deepwater Asset Management.

The EV gap between legacy carmakers and newer rivals is vast. In 2022, Tesla delivered 1.31 million battery EVs. BYD tripled sales from the previous year to reach more than 900,000 (a figure that climbs to almost 1.86 million when plug-in hybrid vehicles are included).

By comparison, the Volkswagen Group, including Audi and Porsche, sold 572,100 battery electric vehicles, while Stellantis (STLA), which makes Chrysler and Jeep, came in at 288,000. Toyota, Ford and General Motors (GM) are even further behind.

New entrants have the jump on technology and the rising Chinese brands boast lower production costs, allowing them to charge lower prices — a huge advantage given that affordability is a major barrier to widespread EV adoption, according to a 2021 survey of EV companies by the International Energy Agency (IEA).

In the EV race reshaping the global auto industry, China is speeding ahead. Japan, South Korea, Europe and the United States — the dominant players for decades — are lagging behind.

Between 2015 and 2022, the world’s largest carmakers — Volkswagen, General Motors, Toyota, Stellantis, Honda (HMC), the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi alliance, Ford, Hyundai-Kia, Geely, Mercedes-Benz and BMW — saw their share of electric car sales worldwide slip from more than 55% to 40%, according to the IEA.

Over the same period, the combined market share of just two companies — Tesla and BYD — has climbed from 20% to over 30%.

Investment bank UBS forecasts that by 2030, Chinese carmakers could see their share of the global EV market double from 17% to 33%, with European firms suffering the biggest loss of market share.

“Those global players with high China exposure are already suffering from the rise of local competitors, especially Volkswagen and General Motors,” the bank’s analysts wrote in a recent note.

Established automakers are now spending hundreds of billions of dollars and setting ambitious targets for EV sales to narrow the commanding lead held by Tesla and Chinese rivals.

As of the end of September last year, car manufacturers and battery makers in the United States, Europe and Asia, excluding China, had announced more than $650 billion worth of investments through 2030 into the EV transition, including manufacturing facilities and battery production, according to Atlas Public Policy, a US-based data and analytics company.

It’s unclear whether those investments will pay off. “When legacy [carmakers] talk about catching up to Tesla or catching up to the leading Chinese automakers, it’s difficult. They simply don’t have the skillset in-house,” UBS analyst Patrick Hummel told journalists on a recent call.

Multi-billion-dollar spending plans also come at a challenging time for the industry, which has had to contend with semiconductor shortages and supply chain snafus for several years. Car sales overall remain well below pre-pandemic levels and profit margins on EVs among established players are slim to non-existent.

There are also doubts over whether consumer demand will rise in line with new supply. Volkswagen plans to temporarily suspend production of some EV models in Germany next month due to weaker demand, a spokesperson for the company told Reuters this week.

“Traditional Auto is in the red when it comes to electrification and they will continue to be in the red… for two-plus years,” Munster of Deepwater Asset Management said recently on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter.

Ford is one such carmaker. In July, it raised its forecast for losses in its EV business for the current financial year to $4.5 billion from an earlier forecast of $3 billion. And it pushed back its target to produce 600,000 EVs a year.

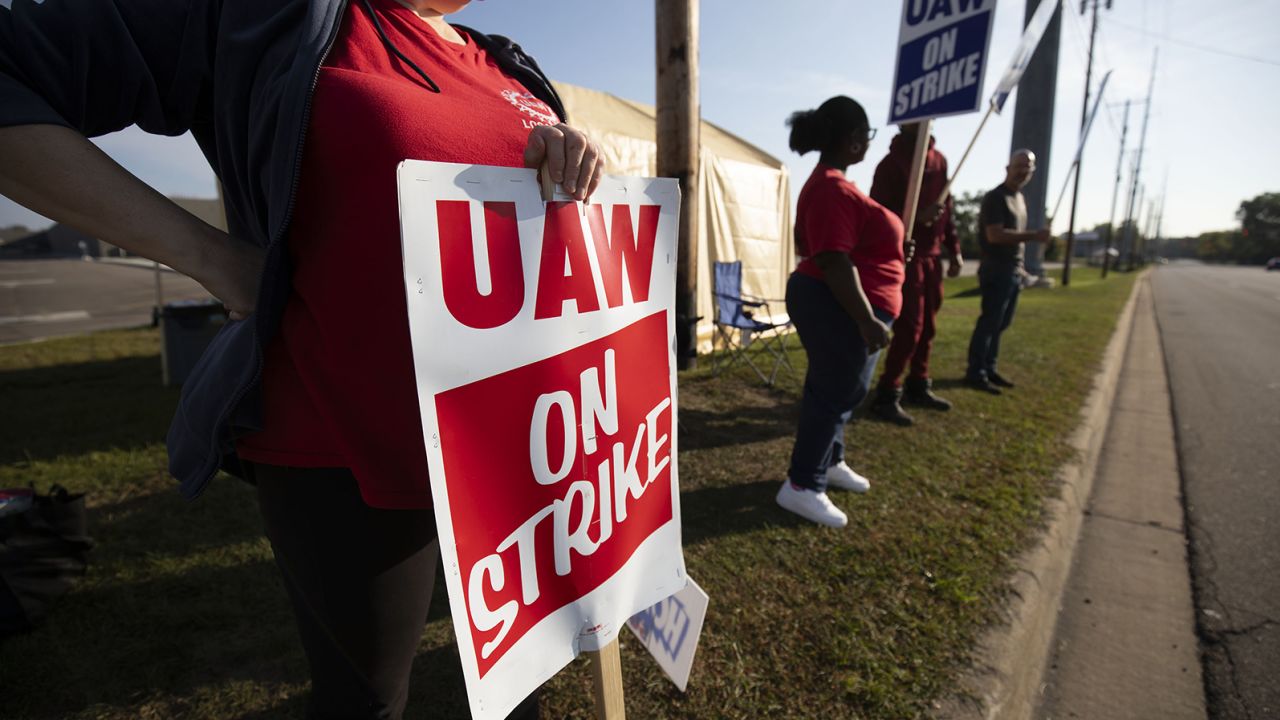

Established automakers may become even less competitive if striking workers at Ford, General Motors and Stellantis win improved pay deals in the United States.

“It’s going to get worse for the Big Three relative to Tesla when it comes to cost per hour of manufacturing labor,” said Munster.

If US automakers give in to union demands — which include sizable wage increases and job protection guarantees — “the EV strategy would essentially be dead on arrival,” Dan Ives, a senior analyst at Wedbush Securities, told CNN.

That’s because the concessions would push up the cost of an average EV by $3,000-$5,000. Passing these cost increases on to consumers would “torpedo” the Big Three’s future business models, he added in a research note.

While they need less labor, EVs cost more to build than combustion engine vehicles because the raw materials for batteries are expensive and hard to come by. Refining manufacturing processes and scaling production also take time.

Here, too, China has the upper hand. It is by far the world’s biggest EV battery manufacturer and dominant in the supply and processing of many critical components needed to make the batteries.

“The overwhelming majority of the battery supply chain is in Chinese hands,” said Daniel Röska, head of EU automotive research at Bernstein, a brokerage. “China… put a much a larger focus on this much earlier than anybody else. Hence the center of gravity is now [there],” he told CNN.

Global automakers have had little choice but to enter into joint ventures with Chinese EV and battery manufacturers. But cooperation has become a more complex undertaking as trade tensions between China and the West rise, and as Western governments push to reduce their countries’ dependence on China.

On Monday, Ford said it would pause work on a $3.5 billion factory in Michigan where it had planned to make EV batteries using technology from China’s CATL, which also supplies batteries to Tesla. When the plan was announced in February, it drew criticism from Republican senator Marco Rubio for the Chinese link.

China is only cementing its leading position with protectionist controls on raw materials critical to EVs and the green energy transition. Its exports of two rare minerals essential for manufacturing semiconductors — abundant in EVs — fell to zero in August after Beijing imposed curbs on overseas sales, citing national security.

A recently announced probe by the European Union into state support for EVs coming from China could make matters worse. EU lawmakers have voiced concerns that government subsidies allow Chinese EV makers to keep prices artificially low, creating unfair competition for European rivals.

If the EU imposes tariffs above its standard 10% rate on imported cars, that could provoke retaliation from China, which would likely harm European carmakers, many of which make a large chunk of their profits in China.

“Adding protectionist measures towards China is kind of like shooting yourself in the foot,” said Röska.

And if Europe wants to lower its carbon emissions, it will need cheap EVs. According to a 2022 report by research firm Jato Dynamics, electric cars sold in China are roughly 40% cheaper than those sold in Europe, and 50% cheaper than in the US.

Chinese carmakers are already setting up manufacturing facilities in Europe as trade barriers rise. The same is bound to happen in the United States, where import duties for cars are set at 27.5%.

“They’re not here but they’ll come here, we think, at some point,” Ford chairman Bill Ford told CNN’s Fareed Zakaria in June.

He also said Ford was not yet ready to compete with Chinese EVs in America: “We need to get ready and we are getting ready.”

Read the full article here