This article analyzes how new monetary technologies have significant potential to disrupt the existing legacy money system over the next years and decades. To the extent that this occurs, it would have macroeconomic implications and would offer investment opportunity along the way.

160 Different Currency Bubbles

There are over 160 different state-issued currencies in the world, and most of them have little or no acceptance outside of their host jurisdictions. Within each jurisdiction, they have a monopoly and thus widespread liquidity and acceptance, but then those attributes fall off very quickly outside of their borders.

In some sense, most currencies are like casino chips or arcade tokens: easily spendable or convertible in that arcade or casino, but of little use or salability anywhere else.

As I write this piece from a U.S. suburb, it would take a nontrivial amount of time and effort to find a conversion point for my paper Egyptian pounds or Norwegian kroner. And if I could somehow find someone willing to take them off my hands for me, perhaps my bank if I happen to be a customer of a national chain (rather than a local bank), it probably would be with substantial fees. That’s the price to pay for very low salability. For all intents and purposes, it stops being money too far out of their borders.

Lyn Alden

U.S. dollars, being the world reserve currency, are different. If you bring dollars with you to most countries, it wouldn’t be too hard to find a broker to convert them for you, or even a merchant to take them directly. The dollar is by far the world’s most salable currency.

The second most salable global bearer asset would likely be a sovereign gold coin. It could be a South African krugerrand or an American gold eagle, but if you bring something like that with you in most places, it shouldn’t be too hard to find a point of conversion.

And then there’s a big gap, with the euro being the next best, a few other large currencies, and then a long tail of duds.

Mostly we just use our Visa card, which is a non-bearer payment method. I swipe my card, and this credit-based signaling mechanism transfers dollars into the merchant’s local currency.

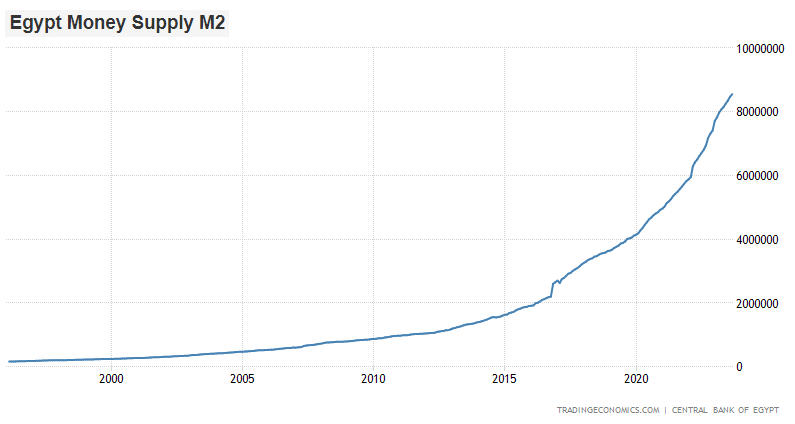

This arrangement of 160+ different currency monopolies can be a real problem depending on what country you happen to be born into. Egypt, for example, is a country that I love and have a second home in, but it has about 20% broad money supply growth per year, and sustained high price inflation because of it.

Trading Economics

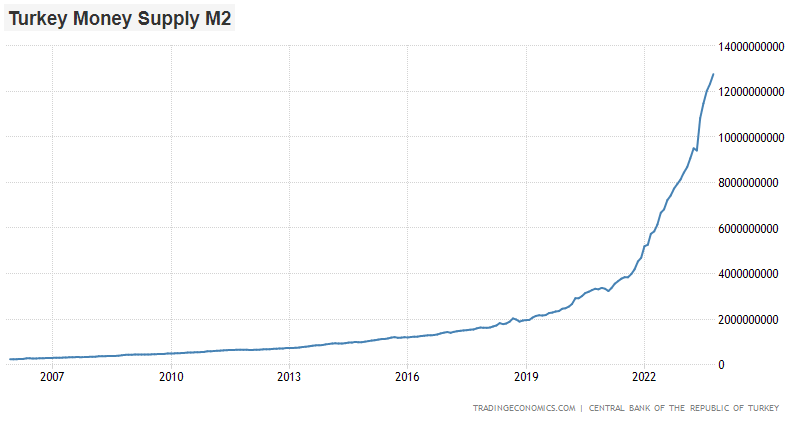

And that seems benign relative to Turkiye, which has increased their broad money supply by about 6x in the past four years:

Trading Economics

Prices are what allow people to coordinate, and when money supply keeps increasing at such a fast rate, it is highly disruptive for economic coordination.

In addition to constantly diluting peoples’ liquid savings with negative real interest rates, this money supply growth constantly dilutes peoples’ wages. If they are not aggressively seeking higher wages year after year, they’re falling behind in international purchasing power terms. If small businesses are not aggressively raising prices, they’re falling behind as well. If landlords are not aggressively raising rents, their real estate investment is unlikely to keep up with international purchasing power.

It’s like being on a treadmill at full-speed, trying desperately to keep up. If you aren’t aggressively seeking out ways to increase your income and protect your savings, you’re getting diluted away.

And it’s especially harsh for the least financially secure people. They’re the ones that often don’t have bank accounts, and are dealing with paper cash without even earning interest on their savings that keep devaluing. Upper-middle classes are more likely to have access to interest-bearing savings accounts that can mitigate some of the dilution, and are more likely to have access to credit, meaning they can basically short the local currency in order to buy property and other assets.

Altogether, it creates a pretty strong effect to continually dilute those who are not arbitraging the money toward those who are.

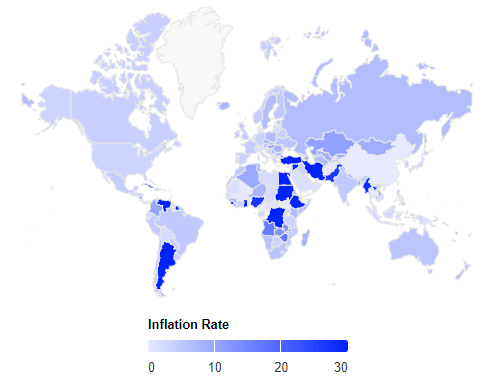

According to Trading Economics, which compiles global inflation data and other economic data, there are over 30 countries that currently have double-digit price inflation, and by rough estimation they have about a billion people in them. In many of these countries, it is a chronic issue.

Trading Economics

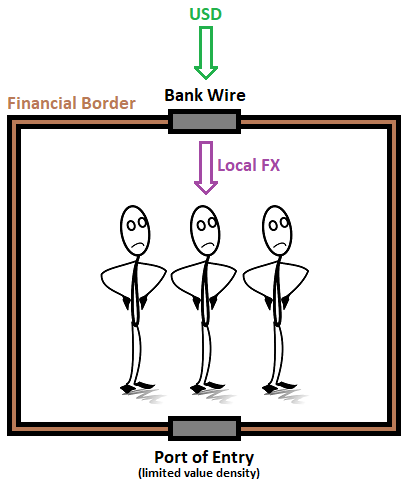

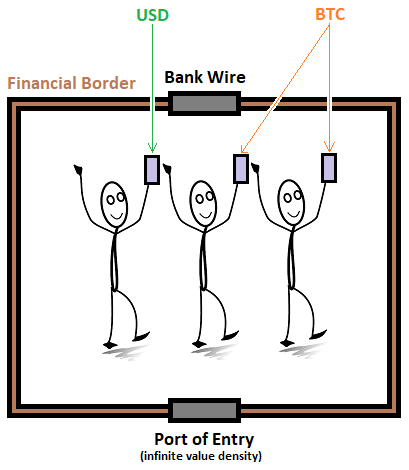

In these countries, it is often hard to get your hands on better money. This is because governments control the only two primary ways to get money in or out.

The first way to bring money in or out of a country is through a port of entry, which today mostly means airports. However, bringing physical cash or gold with you is generally restricted to a rather modest amount.

The second way to is to do to a bank wire transfer, or use a fintech platform that serves as an overlay to a bank wire. Much like ports of entry, governments have tight control over what sorts of wires they allow and whether they force their citizens to convert into their local currency or not. Much like we have a “blood-brain barrier”, national banking systems also have a barrier between their local currency and the outside world, and they can choose how porous or restricted that is. The majority of people in these countries tend to only have bank accounts in local currency, so any payments that they receive get turned into local currency. National governments and banking systems can determine how hard it is to get a dollar bank account, and to what extent (if any) that global dollar-based money transmitters like Western Union can operate within their borders.

If I pay a graphic designer in a given country, then even though they might price their services in dollars, whether they can actually receive in dollars is largely up to their country’s government and financial regulators. In many cases, by the time my payment hits their bank account, it’s in their local currency. In many countries, it can be hard to get a dollar bank account, especially if you’re not wealthy. And even if you do have a dollar bank account, they are sometimes prone to forced conversion back into the local currency if the government has a dollar shortage and a lot of dollar-denominated debt.

Lyn Alden

In other words, governments and corporations in various countries can usually access dollars (unless they are in a sanctioned jurisdiction), but whether normal people in those countries can varies significantly. Those that do access dollars often do so either from 1) relatives who can send them dollar remittances directly with high fees (if allowed by the local government) or 2) on the black market.

In many countries with high inflation, there are street markets for physical cash dollars. People will buy them and literally store them under their mattress. In most countries it’s not a crime to do this, but it is often a crime to be a cash dollar broker. These street transactions are often handled like marijuana transactions basically, like shady little transactions based on word of mouth that come with some risk. All of this effort just because people want some dollars for liquid savings, and either don’t have a direct source for dollar remittances, or those remittances get converted to local currency.

In many countries, the wealthy citizens have offshore bank accounts, offshore brokerage accounts, foreign property, and so forth. All of that relies on credit and a long chain of international counterparties. But then the lower you go down the income and wealth spectrum, the more people are likely to be stuck entirely within the confines of the local currency, and toward the bottom are people that are stuck purely in local cash without even the benefit of interest or credit to offset some of the ongoing inflation. Their wages and their savings are stuck in a constant spiral of dilution, with their economic value and the accumulated fruits of their work constantly taken from them in an opaque way.

Opening the Gates

The inventions of Bitcoin (BTC-USD) and dollar stablecoins are beginning to circumvent this problem. The governments of these countries don’t generally like it, but the people do.

On the Chainalysis crypto adoption index, 16 of the top 20 countries ranked by crypto adoption are classified as developing countries.

In developed markets, people often view bitcoin and stablecoins as a solution in search of a problem, but that’s because our money problems have historically been subtle most of the time. For people in developing countries, their money problems tend to be more obvious, with either high inflation, high financial authoritarianism, or both. The sweet spot for crypto adoption is countries that have some significant tech savvy population centers, and that also deal with bad local money.

With these technologies, I can for example pay a foreign graphic designer directly in bitcoin, dollar stablecoins, or whatever she wants. It goes to her, and goes around her country’s banking system. She can show me a QR code over a video call, and I can pay her on the spot. She can send me an email or DM with a digital address to send money to. If we do this over the Lightning network, it’ll cost next to nothing in fees. There are more and more hubs around the world with merchants that accept bitcoin or stablecoins, or that can convert them into local currency should someone have a need to.

And for ports of entry, someone can write down or memorize twelve words, or store them in an encrypted file in a cloud somewhere (representing their private keys), and bring infinite value density with them. Whenever I see airport signs that say “cash only allowed up to 10,000 USD” I kind of look around and think, “how do they know that none of us in this line have a million dollars worth of bitcoin or stablecoins with us, or that are otherwise accessible to us?”

In other words, the gates were built for an analog world, and the analog walls that those gates protect are becoming increasingly porous. And for most countries, those walls and gates were designed to keep people in; to make it hard for them to access better money. Now with bitcoin and stablecoins it’s easier for them to do so.

Lyn Alden

And only in the past several years has this become relevant, because for nearly the first decade of this technology’s existence, the liquidity and size of these networks was tiny. Only once these networks reached tens or hundreds of billions of dollars in market capitalization, with billions of dollars per day in active volume, do they start to become anything other than a novelty for most people.

Bitcoin now has a market capitalization of about $700 billion despite being in a bear market, and stablecoins have a market capitalization of about $120 billion. The biggest stablecoin issuer is reported by its auditor to hold $56 billion in T-bills, which is more than all but the top two dozen countries as recorded by the U.S. Treasury. They serve as an offshore bank account for the middle class of many countries.

Governments could try to ban their local populations from using these technologies by making it illegal to do so, but it’s hard to enforce. Inflation and capital controls tend to be effective specifically because they are opaque and are happening behind the scenes. But when people finally have a peer-to-peer solution that solves these problems, and a government tries to tell them they can’t, well, that lays their cards on the table and makes it more obvious. In a given country, there are only a handful of major international banks and a longer tail of smaller domestic banks, and they are easy to regulate. But when trying to regulate what individuals do, then the number of enforcement points are in the millions.

When most people, including traditional finance professionals, think of “crypto”, they lump everything together in their head. Bitcoin, stablecoins, monkey jpegs, VC-funded token pump-and-dumps, and scammy yield-farming Ponzis are all categorized similarly. But what I would argue, and have argued for years now, is that the killer app for this technology is money: savings and payments. Bitcoin is a powerful innovation with long-term potential. Stablecoins have been a powerful bridging tool as well.

From a macroeconomic perspective, if these technologies continue to gain adoption over time as they have for 10-15 years now, I think it will eventually make the long tail of these 160+ currency monopolies harder to maintain. In a digitally-connected global economy, people will have much easier access to better money that has global liquidity and salability to it. People everywhere will have more of a choice, as long as they have access to the internet in various ways. Imagine the impact that these technologies could have in five or ten years when they are likely far larger and better understood.

They also allow for micropayments, including international micropayments. Up until fairly recently, it has not generally been possible to send someone the equivalent of ten cents internationally. But for example with the combination of Chaumian e-cash and the Lightning network, that’s possible. Why would anyone want to do that? Well, maybe they want to pay per question for ChatGPT from a developing country, and the monthly subscription is not affordable to them. I’ve played with e-cash apps that make this easily possible. Or maybe more broadly, individual AI agents deployed and operating around the world might want to pay each other across borders in real-time, for things like API usage, GPU usage, or otherwise.

Even for slightly larger remittance-scale international payments (often a couple hundred bucks), the average fee is 6.2%, which harms the people who can least afford to pay it. Open-source money can reduce the overhead for sending cross-border transactions.

Africa has over 40 currencies. Latin America has over 30 currencies. All of these financial borders and conversion barriers act as friction points and economic siloes. And over time they are gradually being more circumvented. They are legacy technology, and they will likely be increasingly hard to enforce in the future.

Bitcoin vs Stablecoins

The main difference between Bitcoin and stablecoins is that Bitcoin is optimized for decentralization and hardness but is currently volatile due to being a novel unit of account, whereas stablecoins are less-volatile because they piggy-back on existing monetary network effects, but are centralized and inflationary.

However, an important aspect of stablecoins is that their central hub can be placed in any good jurisdiction, and then penetrate into other jurisdictions.

For example, dollar stablecoin issuers can operate in the United States, Switzerland, Dubai, or wherever they are welcomed. Other real-world assets can be tokenized too, to the extent that there is market demand for them. For example, there are gold-backed stablecoins operating out of Switzerland and the United Kingdom. There are tokenized T-bills that pass on most of the underlying yield to the holder.

For these stablecoin issuers, what primarily matters is whether their operating jurisdiction welcomes them or not. For example, a stablecoin operator (dollars, gold, or whatever) can operate out of Switzerland, while Argentinians and Turks can use the tokens to protect themselves from inflation, and there’s not a whole lot that the governments of Argentina or Turkey can do about it, as long as the government of Switzerland is fine with it. Argentinians and Turks can make or receive international payments, can buy tokens from brokers and use them for savings, can bring their money portably with them if they move somewhere else, etc. These are all basically digital banknotes.

For this reason, the issuers of these tokens have to comply with laws of their operating jurisdiction, as well as certain international laws (especially if using dollars). That could mean freezing certain assets associated with crime, or blocking most of the use in sanctioned jurisdictions. And of course, the issuer and their auditors must be trusted. Token issuers can go insolvent and default on their users if they make mistakes or act without integrity.

The biggest stablecoin has been operating for over nine years and continues to meet all customer redemptions and maintain its peg, and the second-biggest stablecoin has been operating for over five years and continues to meet all customer redemptions and maintain its peg. That doesn’t mean there’s not solvency risk in the future, though.

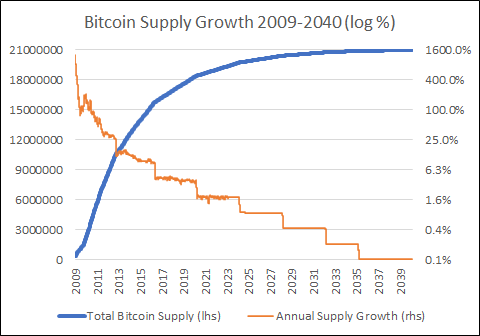

Bitcoin is different in the sense that it has no central hub, and its supply asymptotically approaches 21 million with a hard cap (whereas dollars historically grow in supply at 7% per year and have unlimited eventual supply). Someone who holds their own private keys for their bitcoin truly has a bearer asset that is not reliant on credit; it is only reliant on the decentralized network as a whole remaining operational and uncaptured.

Lyn Alden, with Glassnode Data

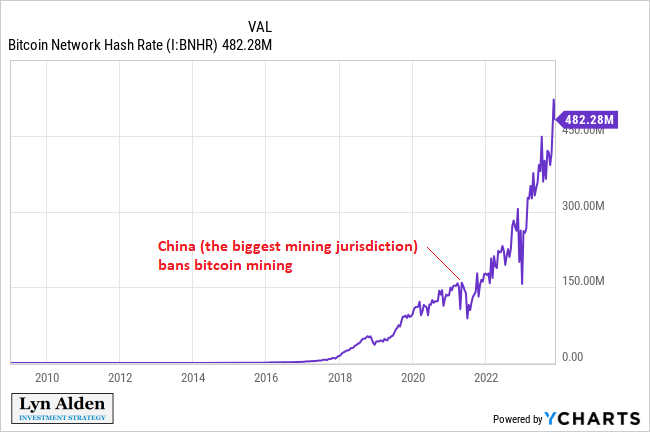

China has “banned” bitcoin mining on multiple occasions but it never really stuck. Eventually in 2021 they went more all-out on it, and were more successful this time. China was the largest bitcoin mining jurisdiction by far, and within a matter of weeks, about half of Bitcoin’s global mining network went offline.

YCharts

Over the next two years, the Bitcoin network basically said, “hold my beer and watch what’s about to happen,” and its mining capacity exploded to the upside, meaning its total network processing power tripled.

Even during the initial shock, the Bitcoin network maintained 100% operational uptime. It just slowed down mildly for a couple weeks until the automatic difficulty adjustment kicked in. If Microsoft or Amazon were given two weeks notice that they had to move all of their servers out of the United States, imagine the magnitude and duration of the disruption of their services that would ensue. But Bitcoin, being more decentralized, maintained 100% uptime. The machines eventually dispersed like a swarm to other jurisdictions and gradually came back online, and the network became more decentralized as a result.

Meanwhile, stablecoins started on a layer on top of the Bitcoin network in 2014, gravitated toward Ethereum, and then gravitated toward Tron. Basically, since they are centralized anyway, they go to wherever fees are cheap, settlements are fast, and liquidity network effects are present. And among stablecoin issuers, only the largest issuers tend to capture most of the market share, due to token-level liquidity network effects.

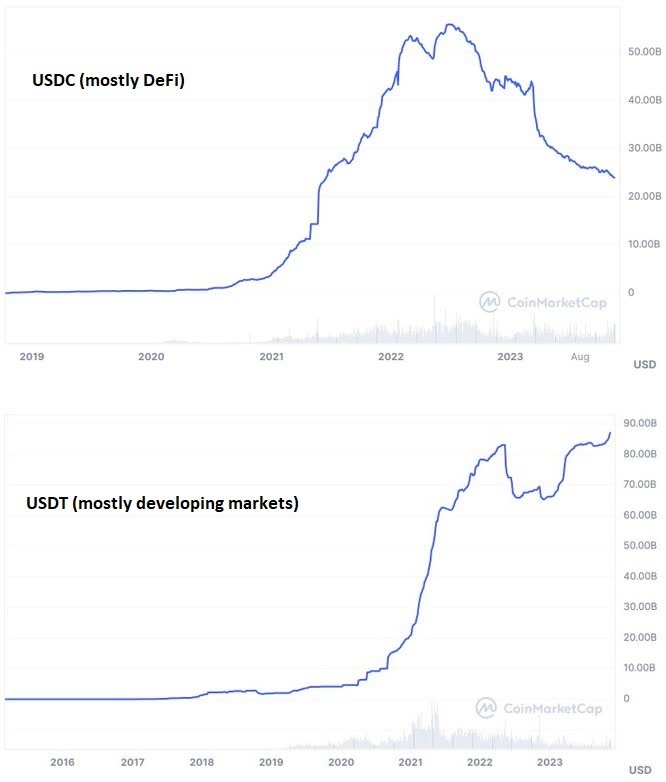

Historically, the two main use cases for stablecoins have been for 1) speculation and 2) utility.

-The speculation use-case is mainly in offshore exchanges or DeFi projects. In offshore exchanges, they are often used as a unit of account and for holding cash balances in active crypto trading. In DeFi projects, they are also used for leveraging and yield farming. A lot of this usage still happens on Ethereum.

-The utility angle use-case is mainly around developing countries for use as payments and savings, as previously described. A lot of this usage has gravitated toward Tron, where it’s cheaper.

And amid the current crypto bear market that has been running for 2+ years since the top of the market cycle in 2021, the DeFi use-case has been stagnating, but the developing market payments/savings use case continues to gain strength. This can be somewhat visualized by looking at the different market capitalizations of USDC (often used by wealthier traders, and often on Ethereum) vs USDT (often used in developing countries, and often on Tron):

Coin Market Cap

In his recent documentary, journalist Peter McCormack traveled to Argentina to interview people about their ongoing inflation problem, and explored how people there specifically want USDT on Tron during dollar conversions (with that chapter starting at the 10:46 mark).

Should someone hold their entire net worth in stablecoins? No. They’re vulnerable to changes in regulation by the United States, and rely on centralized international issuers. But the way a lot of people use them in inflationary environments is that they’ll have a bit of local currency for near-term expenses, a moderate amount of stablecoins for intermediate-term liquid savings, and then other assets like bitcoin for longer-term liquid savings, or rely more heavily on less-liquid assets like real estate.

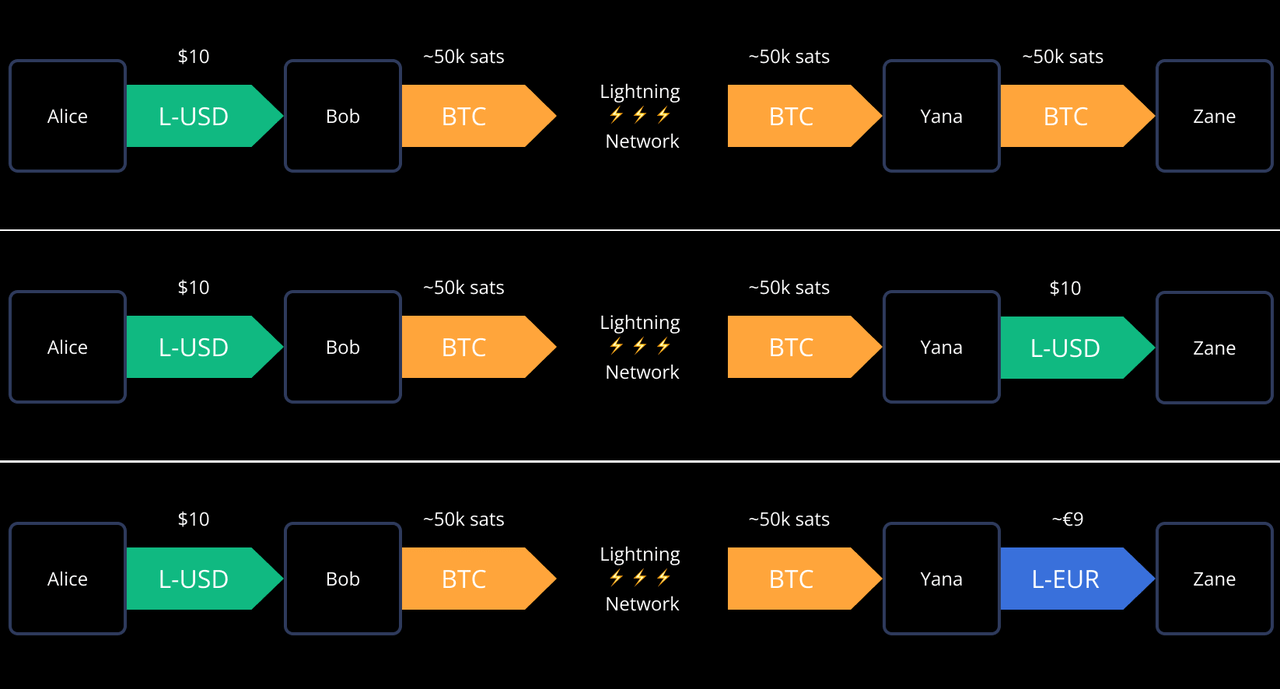

Announced by Lightning Labs in 2022, Taproot Assets has the potential to create yet another shift of where stablecoin usage ends up, and bring some of it back to Bitcoin. The Bitcoin main-net beta version of Taproot Assets went live last month, and it is expected to be usable on Bitcoin’s Lightning network soon. If it is successfully deployed and adopted, this will allow stablecoins to flow more natively across existing Bitcoin/Lightning network liquidity.

For example, if or when this gets deployed, someone can have a Taproot Asset stablecoin channel on the periphery of the Lightning network, send a payment to someone through the Lightning network’s core Bitcoin-denominated liquidity, and then the receiver on the other side could receive bitcoins, could receive stablecoins of the same currency, or could receive stablecoins of another currency. Many wallets can let people hold bitcoin and stablecoins and thus make the choice on what they want to hold for a given purpose.

Lightning Labs

Basically, this overall technology from the Bitcoin network itself to stablecoins on various networks gives the world a new form of harder decentralized global self-custodial money, and then also gives people in developing countries access to the best developed-country currencies and assets, and market participants can sort out what ratio of those things makes sense for them.

Realistic Adoption Patterns

Skeptics often point out that Bitcoin is volatile. That’s a fair point, and that’s also why stablecoins have a significant degree of market-driven popularity today despite their ongoing supply inflation and their reliance on third-party operators.

But realistically, an emerging form of money can’t have its market capitalization go from being worth zero to being worth trillions of dollars without upward volatility, and with upward volatility will come leverage and periods of downward volatility. I would argue that over-emphasizing volatility as a problem, is to miss the forest by focusing too much on the trees.

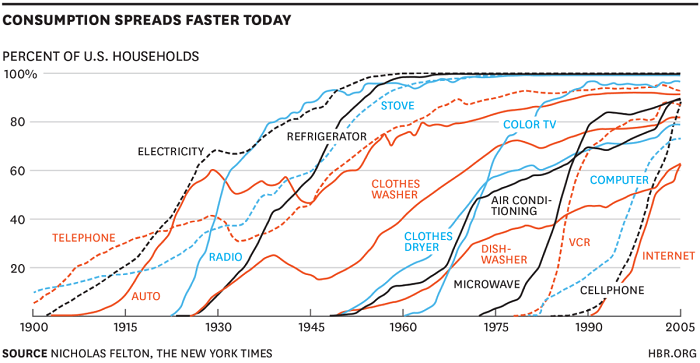

Most technologies have a pretty smooth adoption curve. When people get electricity in their region and their house, buy a radio, buy a television, start using the internet, or start using smartphones, they rarely ever go back to not using them. They don’t de-adopt a technology. Outside of economic calamities (like the Great Depression), the adoption curve tends to be smooth and up. Sometimes it takes as little as 15 years, and sometimes it takes upward of 45 years, but it rarely moves backward.

Nicholas Felton, NYT, retrieved from HBR

If we were to extend that chart into the present day, we’d see similar smooth curves for media streaming, social media, smart phones, and AI.

But adoption of new, decentralized money is inherently different. If it starts to adopt and go up too smoothly, people will leverage it, and thus they will turn into forced-sellers if the price goes down. Other people will get overly-excited and buy too much during a period of mania without fully understanding what they’re buying. Some people will build outright frauds or Ponzi schemes on top of it or adjacent to it. And then that period will exhaust itself and create a ton of downward volatility and liquidations. Unlike most technologies, some people will become disillusioned with it and de-adopt it. They buy at the top, and sell at the bottom, and wash their hands of this technology, at least for a while.

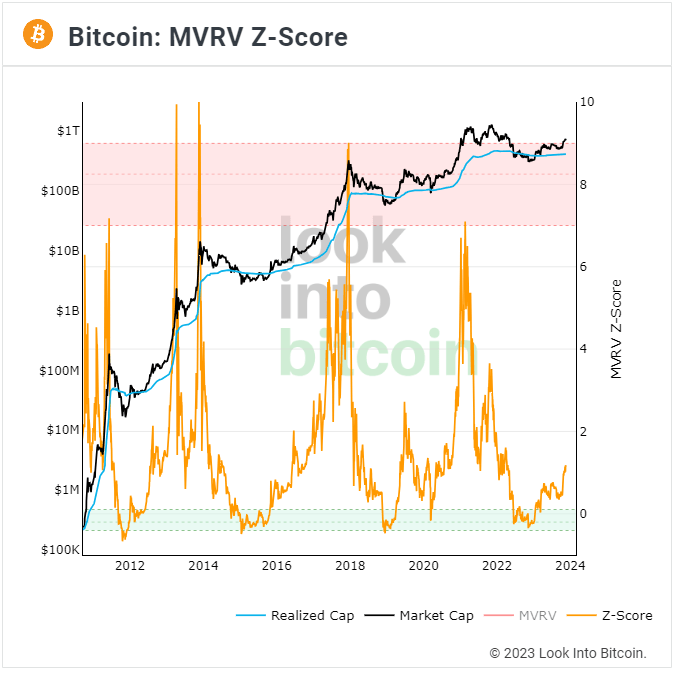

I’m not aware of any other asset that has drawn down over 75% on three separate occasions and eventually went back to much higher highs. Bitcoin has done this, and in the next couple of years it might do it for the fourth time.

Look Into Bitcoin

Every time Bitcoin has one of its manias over its 15-year lifecycle so far, people compare it to the infamous tulip bubble, but the thing about the tulip bubble is that it was brief and didn’t keep coming back. Like most bubbles, it was one-and-done.

Usually if an investment falls 75%, it never sees new all-time highs again. Some of the best-ever investments, like Amazon stock, often manage to come back from that magnitude of a drawdown once, like after the Dotcom bubble. Bitcoin has uniquely done it three separate times over almost 15 years, and is likely working its way out of the fourth as I write this.

But naturally this elongates the adoption pattern. Rather than taking one decade to reach its eventual market saturation as some fast-growing (15-year) technologies do, to the extent that it’s successful, it’ll take multiple decades. Judging from where we are now, it’ll be over two decades at the bare minimum, and I would assume over three decades.

Meanwhile, Bitcoin also faces periods of market dilution from thousands of other cryptocurrencies. Whenever there is a raging bull market, people introduce and market other types of coins, claiming to be better in some way. In reality, they usually sacrifice some degree of decentralization or security to maximize some other variable like speed or programmability. So far, out of over 20,000 cryptocurrencies, only about three of them have ever made a higher-high in bitcoin-denominated terms in the next market cycle. Instead, they tend to have their 15 minutes of fame, and then stagnate forever. Bitcoin has required time to shake off these token dilutions in each cycle, as its own liquidity and network effect grind higher and higher.

And we should visualize this in terms of liquidity as well. When bitcoin had thousands of dollars worth of daily trading volume, someone couldn’t just buy a million bucks worth of it. It would barely be on their radar. Similarly, when bitcoin had millions of dollars of daily trading volume, someone couldn’t just buy a billion bucks worth of it. Now that it has billions of dollars worth of daily trading volume, the largest pools of capital still can’t just buy a ton of it right away. The larger its market capitalization and liquidity get, the more capable the network becomes at attracting even larger pools of capital.

With at most a couple hundred million people that own it globally based on the reported number of accounts at the world’s largest exchanges, Bitcoin has something like a 2-3% adoption rate or less. But most of that “adoption” is just having a little bit of it sitting on an exchange or custodian, that they treat as a speculation. More directly, there are about 4.5 million addresses with at least 0.1 bitcoins (currently worth about $3.7k USD), and since some people have many addresses, it means significantly fewer than 4.5 million people directly self-custody at least 0.1 bitcoins.

If the day comes where bitcoin is held by a third of people or half of people in the world in some capacity, it’ll likely be a lot less volatile, both in terms of upward volatility and downward volatility. For now, it’s still in the early adopter phase for those willing to consider the future and take on some degree of uncertainty, and shakes out people who buy too much relative to their volatility tolerance, or people who leverage it too greedily.

And as long as there are legal tender laws which tax most purchases or sales of non-legal-tender assets, then the overall volume of bitcoin-denominated medium-of-exchange usage is likely to come later.

People first turn toward it as a type of globally-portable self-custodial savings, since that is the bigger problem that most people face, and then only start using it for payments if it solves a particular need that they have. What bitcoin represents for many holders at this stage of its adoption cycle is optionality; they have a globally-portable and rather liquid asset that, almost wherever they bring it in the world, they can find a merchant in an urban center who would accept it for goods and services, or can find a broker to convert it into the local fiat currency.

Unlike most investments, I personally treat my cold-storage bitcoin holdings like money, rather than like an investment. I’ve recommended it and owned it since April 2020 at $6,900 per coin, and asking me when I would sell the bulk of my bitcoin is like asking when I would sell the bulk of my dollars. As long as I work in the United States and the dollar is their legal tender, I’ll be using dollars in some capacity. Similarly, as long as the Bitcoin network continues to be decentralized, secure, and the best at what it does, I’ll be using bitcoin in some capacity. When would I sell some of my globally-portable liquid money with a hard-capped supply? Either if there is a problem with the network, or because there is something I want to buy with my money that appeals to me more than savings, like a consumer good or an investment security.

So what do I monitor when it comes to the Bitcoin network? I look for technical risk (anything that might be able to damage its decentralization and security), I look for regulation risk from major economic powers that could set its adoption back a bit longer, and I look for periods of mania.

If the day ever comes where it has moved beyond these risks, it certainly won’t be at today’s price anymore. Today’s price is a manifestation of market participants’ ongoing education about the asset and then that market’s assessment of the forward probability of the Bitcoin network continuing to succeed through various challenges. And as such, I size my position size with those considerations in mind.

Read the full article here