If a strange photo has recently stopped you in your tracks while scrolling your Facebook feed, you’re not alone.

Users who once came to Facebook to connect with friends and family are increasingly complaining of random, spammy, junk content — much of it apparently generated by artificial intelligence — showing up in their feeds.

Sometimes it’s obviously fake, AI-generated images, like the now-infamous “Shrimp Jesus.” Other times, it’s old posts from real creators that look like they’re being reshared by bot accounts for engagement. In some cases, it’s pages sharing streams of seemingly benign but random content — memes or movie clips, shared every few hours.

But the spam is more than just an annoyance; it can also be weaponized. Some spam pages appear designed to scam other users. In extreme cases, spam pages that gain a following can eventually be used, for example, by foreign actors seeking to sow discord ahead of elections, according to experts who study inauthentic behavior online.

The surge coincides with an intentional strategy shift at Facebook in the past few years. The company de-emphasized current events and politics in the wake of claims it had contributed to election manipulation and real-world violence. Feeling the heat from the rise of TikTok and its emphasis on entertainment over social connections, Facebook re-designed users’ home feeds into a “discovery engine” in the hopes that people would engage with content they might not otherwise see.

But the push for more “discoverable” content has led to an algorithm that regularly pushes vapid, often misleading, computer-generated content.

The change has been palpable. AI-generated or recycled meme content has appeared on Facebook’s quarterly most viewed content list. Posts with obviously AI-generated images and confusing captions sometimes receive thousands of likes and hundreds of comments and shares.

Bad actors and engagement farmers are only too happy to fulfill Facebook’s demand for new content, experts say. And the proliferation of AI tools has made it far easier for them to quickly crank out huge volumes of fake images and text.

“It’s a really interesting thing that a lot more people are starting to talk about because it’s this random, kind of vanilla problem now, but obviously there are theoretical, long-term concerns,” said Ben Decker, CEO of online threat analysis firm Memetica.

Facebook parent company Meta, for its part, works “to remove and reduce the spread of spammy content to ensure a positive user experience, offering users controls over their feed and encouraging creators to use AI tools to produce high-quality content that meets our Community Standards,” spokesperson Erin Logan said in a statement. “We also take action against those who attempt to manipulate traffic through inauthentic engagement, regardless of whether they use AI or not.”

Before I started reporting this story in July, my Facebook feed felt pretty normal, featuring baby photos from college friends and listings from Facebook Marketplace.

But, curious about the complaints, I started clicking on whatever content I did see that seemed odd, and the algorithm kicked in. Now, weeks later, nearly every third post on my feed appears to be so-called “AI slop.”

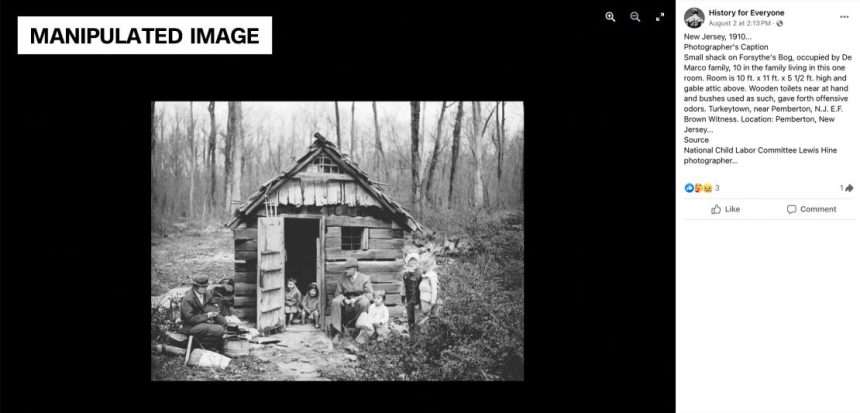

One recent example: a black-and-white image showing a shack in the woods with a family sitting out front, shared by a page called “History for Everyone.”

At first glance, the post looks like something you might find in a history book. But upon closer inspection, the people in the image have blurred, undefined facial features, and the children’s hands and feet seem to disappear into the landscape around them — hallmarks of AI-generated images.

The post’s caption claims the image was taken in 1910 in New Jersey at a “small shack on Forsythe’s Bog, occupied by De Marco family, 10 in the family living in this one room,” by National Child Labor Committee photographer Lewis Hine. Curious, I copied the full caption into Google, which pointed me to the real caption of an entirely different photo that had been published by the Library of Congress.

I plugged the Facebook image into a Google reverse image search, and the only other places it appeared online were two other, similar Facebook groups called “Past Memories” and “History Pictures.”

It’s impossible to say definitively how the image was created, but CNN’s photo team ran it through AI-detection software — which is still in early testing — and found “substantial evidence” it had been manipulated. Hany Farid, a digital forensics expert and UC Berkeley professor who has studied AI, added that the image appeared to be AI-generated and may have been created by using the caption of the real, historical image as the AI prompt, potentially to avoid copyright infringement.

The group that shared the post, “History for Everyone,” is managed by a page by the same name, which was created in 2022 and previously changed its name from “Cubs” and “Chikn.Nuggit.” The page did not respond to a direct message.

The History for Everyone post is illustrative of a lot of the content that’s come across my feed — uncanny, bizarre, but also seemingly benign.

Other examples include a page called “Amy Couch” that also shares “historical” photos, with an apparently AI-generated profile photo that shows a woman with one giant tooth where her two front teeth should be. Or an art and history page for an “artist” called “Kris Artist” whose profile photo I traced back to a real social media influencer who told me over email: “That is definitely not my account but they are using my picture.”

When I messaged the “Kris Artist” page, I received what appeared to be an automated response: “Hi, thanks for contacting us. We’ve received your message and appreciate you reaching out. Please Join our Group.”

After I flagged the History for Everyone post, as well as the Amy Couch and Kris Artist pages, to Meta, it removed them for violating its spam policy.

It’s not clear exactly how much of this content exists on Facebook. But there may be lots of people seeing it. The “History for Everyone” page has more than 40,000 followers, although individual posts often receive just a handful of interactions.

Researchers from Stanford and Georgetown earlier this year tracked 120 Facebook pages that frequently posted AI-generated images — and found the images collectively received “hundreds of millions of engagements and exposures,” according to a paper released in March, which has not yet been peer-reviewed.

“The Facebook Feed … at times shows users AI-generated images even when they do not follow the Pages posting those images. We suspect that AI-generated images appear on users’ Feeds because the Facebook Feed ranking algorithm promotes content that is likely to generate engagement,” researchers Renee DiResta and Josh Goldstein wrote in the paper. They added that often the users engaging with that content didn’t seem to realize it was AI.

Experts who track this kind of online behavior say there are likely several different kinds of actors behind the Facebook spam, with varying motives.

Some just want to make money, for example through bonus payments that Facebook pays out to creators posting public content. There are dozens of YouTube videos teaching people how to get paid for posting AI content on Facebook — as tech news site 404 Media reported earlier this month — with some claiming they make thousands of dollars each month using the tactic.

“Even in the realm of the political, the tactics of manipulators have long been previewed by those with a different motivation: making money. Spammers and scammers are often early adopters of new technologies,” the Stanford researchers wrote.

On other pages, scammers use the comments as a place to hawk sham products or collect users’ personal information.

In some cases, what looks like a harmless account sharing mostly random content will slip in occasional misinformation or offensive memes, as a way of evading Facebook’s enforcement mechanisms. “If something looks just like a run-of-the-mill spam campaign, it might not trigger the company’s top investigators … and so it might go undetected for longer,” said David Evan Harris, an AI researcher who previously worked on responsible AI at Meta.

Harris added that there is also an online market for “aged” Facebook accounts, because older accounts are more likely to appear human and evade the platform’s spam filters.

“It’s like a black market, basically, you can sell someone 1,000 of these accounts that are all five years or older, and then they can turn those into a scam or an influence operation,” Harris said. “This is something you see in elections: Someone might make a Facebook group that’s like, ‘everybody loves cheeseburgers,’ and the group posts images of the best cheeseburgers every day for two years, and then all of a sudden, a month before an election … it becomes a ‘vote for (former Brazilian President Jair) Bolsonaro’ group.”

With AI tools, bad actors no longer need lots of people to rapidly produce reams of fake content — the technology can do it for them.

For Facebook to identify all of the AI-generated images getting uploaded each day without making mistakes would be challenging, “particularly at a time when this technology is moving so incredibly fast,” Farid said. Even if it could, “that doesn’t mean you should ban all AI generated content, right? … It’s a very subtle question on policy,” he said.

Earlier this year, Meta said it would add “AI info” tags to content created by certain third-party generators that use metadata to let other sites know AI was involved. Meta also automatically labels AI-generated images created with its own tools.

However, there are still ways for users to strip out that metadata (or create AI images without it) to evade detection.

Meta may also be hampered by a smaller team dedicated to addressing fake content, after it — like other tech giants — trimmed its trust and safety staff last year, meaning it must rely more on automated moderation systems that can be gamed.

“Digitally savvy social media communities have always been one and a half steps ahead of trust and safety efforts at all platforms … it’s almost a cat and mouse game that never really ends,” Harris said.

Read the full article here