Co-produced by Austin Rogers.

There is always a lot of noise in the financial media about the state of the economy, but most of it is, to quote Shakespeare, “sound and fury signifying nothing.”

So, let’s look at some data points to try to gain clarity on the state of the economy and specifically the health of the American consumer.

What we find in the data is a steadily softening economy that has so far managed to avoid recession but is losing its last few remaining growth drivers. The huge savings buffer built up during the pandemic years has steadily depleted for most Americans, causing higher prices to increasingly eat into consumer spending power. The magnitude of these savings has delayed the recession, but we still view a near-future recession as highly likely.

As we have explained in the past, we think a recession would be a net benefit to real estate investment trusts, or REITs (VNQ), because it would almost certainly cause interest rates to fall.

The primary cause of REITs’ poor performance over the last year or so has been rising interest rates, so the reversal of rates’ trajectory from rising to falling should give REITs a huge boost.

A Tale of Two Consumers

Here are some highlights to consider:

- The San Francisco Fed predicts that pandemic-era excess savings will be fully depleted this month.

- Mandatory payments on nearly $1.8 trillion in student loans is about to resume in October.

- The personal saving rate is at its lowest level since 2008.

- Credit card debt is hitting new all-time highs.

- Slightly over 60% of Americans report that they are living paycheck-to-paycheck.

- A wave of retail theft is sweeping the nation.

Pundits in the financial media often assert that the consumer is strong, pointing to rising household net worth from buoyant homes and stock markets.

The problem with this thinking is that it succumbs to the tyranny of averages. That is, talking about the “average American consumer” ignores and downplays the widely varying financial conditions of different consumers.

There are really two basic categories of American consumers:

- Affluent

- Paycheck-to-Paycheck (P2P).

| AFFLUENT | PAYCHECK-TO-PAYCHECK |

| Spends mostly on services and durable goods | Spends mostly on essential goods |

| Ample savings | Little to no savings |

| Regularly able to save from income | Able to save little to nothing from income |

| Little to no consumer debt | Rising consumer debt, e.g. car payment, credit cards, etc. |

| Likely to own home | Likely to rent |

| Spends less than 20% of income on housing | Spends over 30% of income on housing |

| Well-educated and connected with successful people | Little education and disconnected from successful people |

| Directly or indirectly owns stocks | Little to no exposure to the stock market |

| Student loan payments nonexistent or negligible, likely to come from savings | Student loan payments likely to eat into other spending |

There are probably other basic differences, but you get the idea.

About 30-40% of Americans are Affluent consumers, while 60-70% are more or less living P2P.

From mid-2020 through 2022, both types of consumers were flush with cash from Uncle Sam and happy to spend it. This provided fuel for the inflationary surge while also driving business expansion, job growth, and demand for commercial real estate. Consumer inflation translated into rent growth.

But in 2023, that situation is changing. Affluent consumers are going back to their normal, pre-COVID spending patterns.

Meanwhile, P2P consumers are increasingly feeling the pinch of inflation and depleted savings.

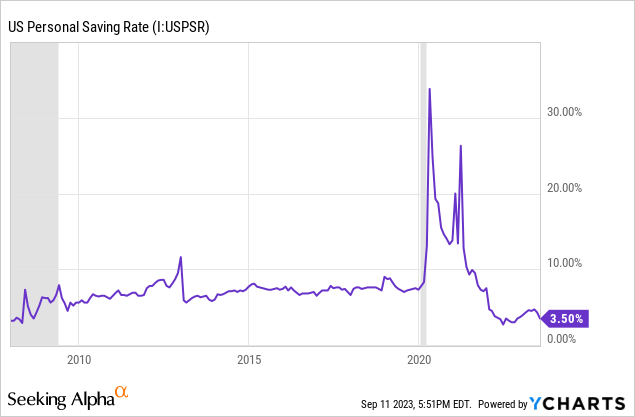

On average (including both Affluent and P2P), Americans are only able to save 3.5% of their income, which is less than before COVID-19. In fact, it’s the lowest level since 2008.

YCHARTS

This average means that the Affluent consumer is saving something north of 3.5% of their income, while the P2P consumer is saving virtually nothing or even spending more than their income (negative saving rate).

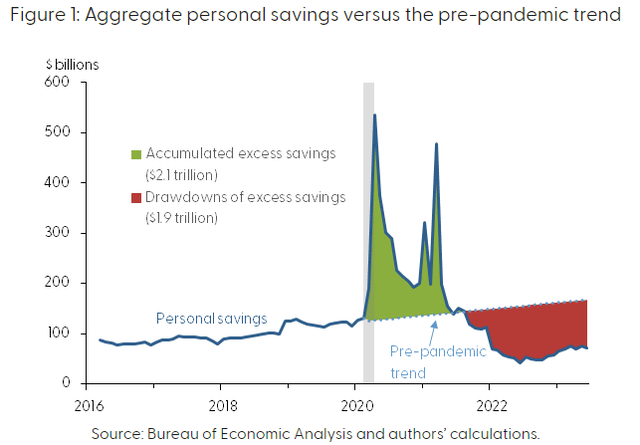

When looking at total personal savings, we can see the huge spikes in pandemic-era savings in 2020 and 2021, followed by a steep drop in savings in late 2021 that continues to today.

San Francisco Federal Reserve

According to the San Francisco Fed, 100% of the pandemic-era excess savings will be depleted by the end of this month (September 2023).

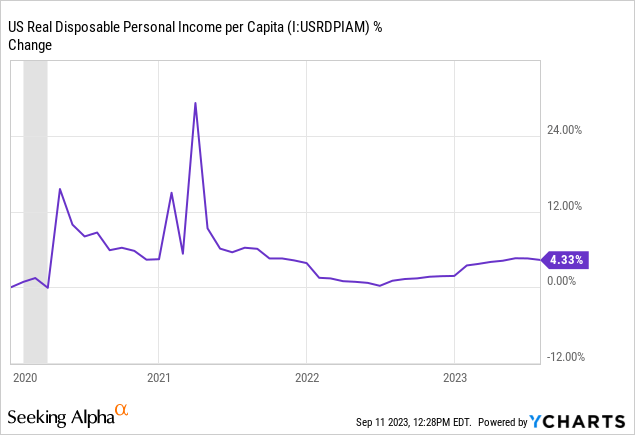

And now, rather than consumer spending being fueled by pent-up savings, consumption will have to be funded by growth in disposable income. This has been minimal in a real (inflation-adjusted) sense since government stimulus efforts ended in 2021.

YCHARTS

Since the beginning of 2022, real disposable personal income per capita has increased a total of 1.2% (less than 1% on an annualized basis).

Again, it’s useful to differentiate here between the Affluent consumer and the P2P consumer.

Amid the severe labor shortage of 2021 and 2022, the lower-income worker saw their wages soar higher as employers competed to fill jobs. But in 2023, that labor shortage has become less acute, leading to smaller wage increases. The labor force participation rate is now only 60 basis points lower than it was immediately preceding the COVID outbreak, while aggregate demand has pulled back from its peak level.

Thus, without the benefits of excess savings or high wage growth to act as “shields” from inflation, the P2P consumer has rapidly weakened this year.

This explains a few major economic phenomena present right now.

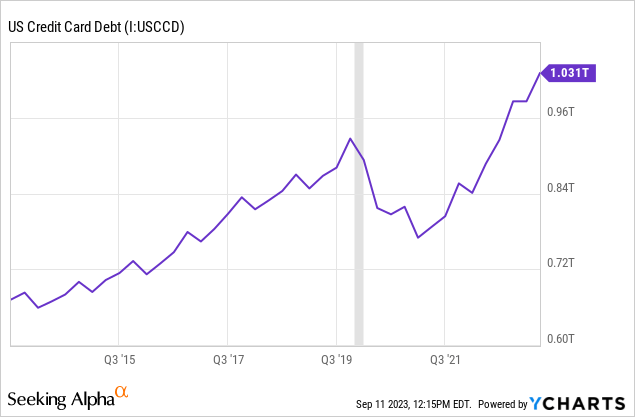

For example, if “the American consumer” is so strong, why is credit card debt soaring to new highs?

YCHARTS

It’s because the P2P consumer gains very little benefit from buoyant home and stock prices. The vast majority of home and stock value is owned by the Affluent, as are most other assets.

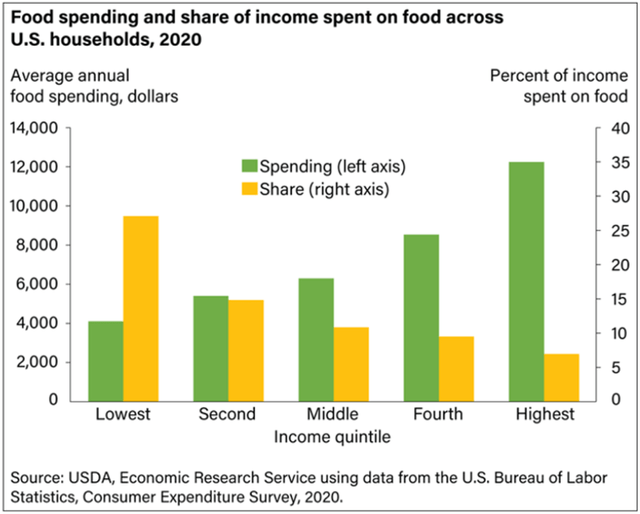

Besides, despite spending more money on essential items like food than the P2P consumer, only a minority of the Affluent’s income goes toward spending on essential items, whereas a sizable chunk of the P2P’s income goes toward essential items.

USDA

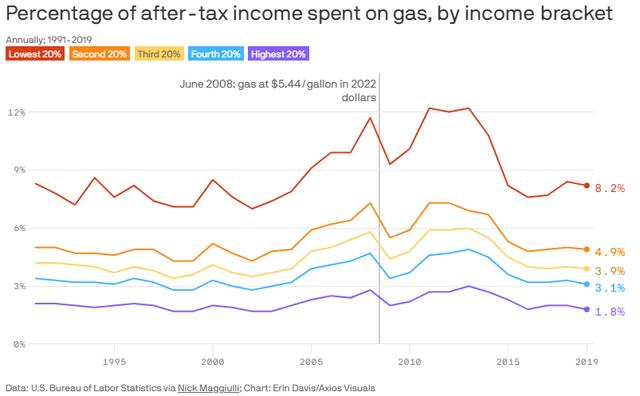

The same holds true for gasoline:

Axios

This is only becoming more true over time, as Affluent consumers increasingly drive electric vehicles, spending $0 on gas and little to no money on regular car maintenance while collecting a $7,500 tax credit from the government.

For the most part, the surge in credit card debt is coming from P2P consumers who no longer have savings buffers, aren’t getting as high of wage increases, and can’t dip into retirement accounts to bridge the gap between their cost of living and income.

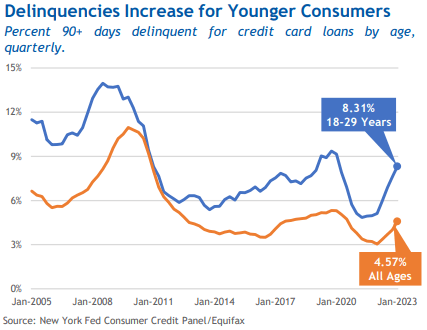

As another data point demonstrating this, consider that as of earlier this year, the rate of credit card debt delinquencies has spiked far more for young people (18-29 years) than for older people.

American Bankers Association

Younger people are far more likely to be P2P consumers, while older people are more likely to fall into the Affluent camp.

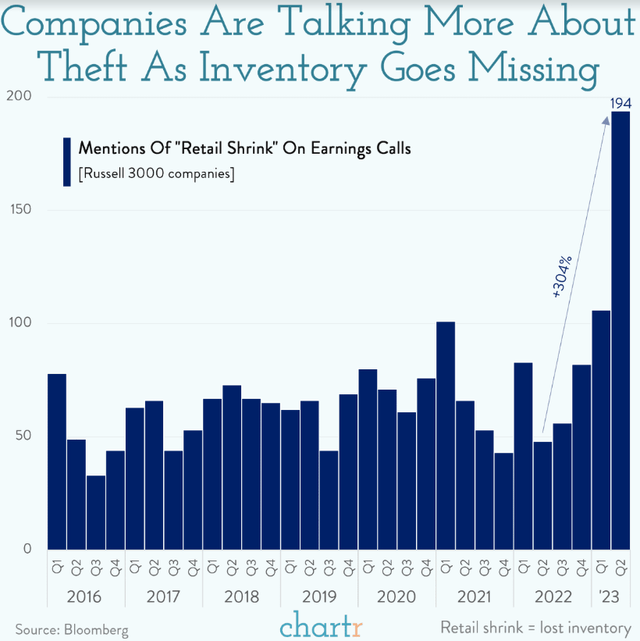

All of the above goes a long way in explaining the striking surge in retail theft.

CHATR

Of course, theft has increased the most in jurisdictions in which local and state governments have chosen not to prosecute petty crimes, including shoplifting under certain limits.

But this has merely created the opportunity. The need for retail theft has clearly grown, as exemplified by the increasing theft of essential grocery items like bread, meat, baby formula, and over-the-counter drugs. Even if shoplifters are mostly reselling these items, there is clearly demand for lower-priced essential items at flea markets and online resale websites.

In short, the pandemic-era savings glut has been fully depleted, there does not appear to be a wage-price spiral forming, and P2P consumers seem to be hurting.

If you believe the U.S. economy will avoid recession and that growth will soon reaccelerate, ask yourself this: what will be the next catalyst of growth?

Over the past few years, economic growth has been fueled by cash-rich consumers, both Affluent and P2P. But that era appears to be over.

Leading Economic Indicators Still Point To Coming Recession

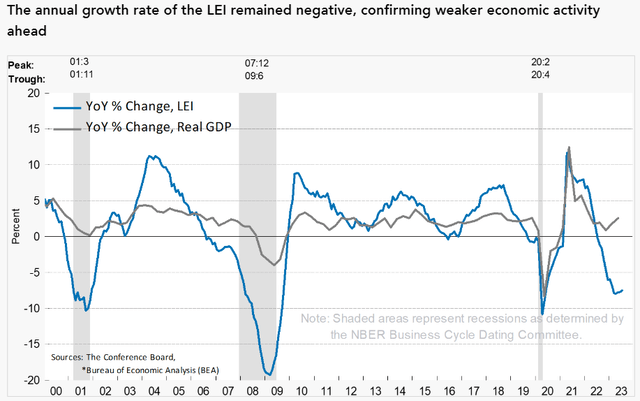

The Conference Board’s Leading Economic Indicators index continues to show a deeply negative reading, indicating that a decline in economic activity is highly likely in the coming months.

The Conference Board

Notice that in the quarters leading up to the recessions in 2001 and 2008-2009, the LEI was deeply negative even while real GDP growth held up. The same holds true today. This doesn’t mean that the economy is reaccelerating or that we will definitely avoid a recession, just that no recession has shown up yet.

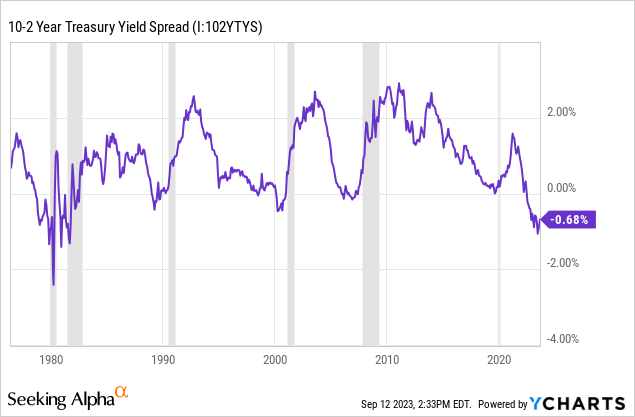

Perhaps the clearest forward indicator of an oncoming recession is the inverted yield curve. This refers to the rare condition in which the 10-year Treasury interest rate (US10Y) is lower than the 2-year Treasury interest rate (US2Y).

YCHARTS

In every case of a meaningful inversion of the 10-year and 2-year Treasury yields, such as we have today, a recession has followed.

And you might notice that the official beginnings of recessions don’t come at the most inverted point but rather a little bit after the curve has begun to un-invert. In fact, recessions tend to begin as the yield spread hits zero or even after it has already steepened a little above zero.

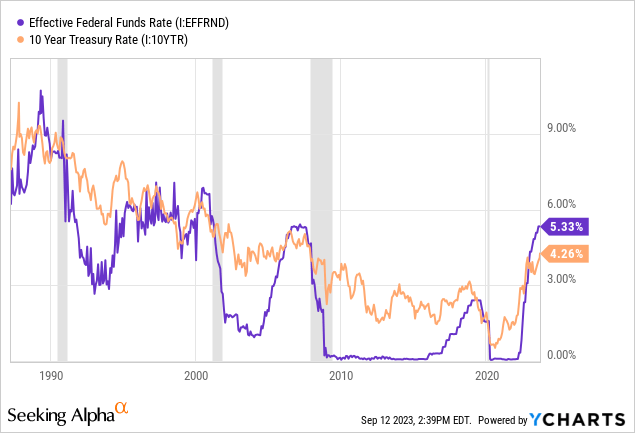

We can see this starkly when comparing the Fed’s key policy rate — the Federal Funds Rate — with the 10-year Treasury yield. Aside from a brief instance in the late 1990s, every instance in recent history of the Fed Funds Rate climbing above the 10-year Treasury yield has resulted in a recession within a year or so.

YCHARTS

That inverted yield curves have historically preceded recessions isn’t merely correlation. There’s causation here too.

The economy simply doesn’t function properly when short-term interest rates are higher than long-term interest rates.

For example, the banking business model breaks down. Depositors move their money into higher yielding vehicles, raising banks’ cost of funds to such a degree that they are unable to earn a sufficient risk-adjusted spread on loans. Thus, credit conditions tighten, and banks pull back on extending loans to businesses and consumers.

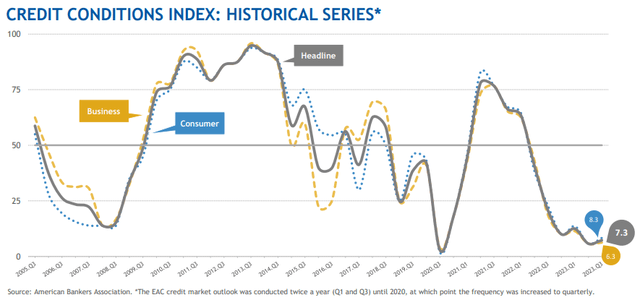

Again, we see this show up in the data. The American Bankers Association’s Credit Conditions Index for Q2 2023 shows a tighter credit environment for both businesses and consumers than at any time since just before the Great Financial Crisis (with the sole exception of the beginning of COVID-19).

American Bankers Association

A reading of “50” indicates that credit conditions are neither tight nor loose. Readings below 50 mean that bank economists expect credit conditions to weaken in the next few quarters. Readings deeply below 50 indicate that credit conditions are expected to get significantly worse.

Plus, considering the higher debt loads in both the private economy and the federal government, there is a strong case to be made that higher interest payments will gradually crowd out other, more productive uses of resources.

For example, in Q2 2023, US federal government interest payments reached 3.62% of GDP — the highest level since 1999.

While this never stopped the federal government from spending, the same thing is happening in the corporate sector. Interest expenses are rising for businesses of all sizes, which will cause (and already has caused) a pullback in spending as businesses prioritize deleveraging over growth.

The Conference Board expects a mild recession to begin in Q4 2023 and continue through Q1 2024. That seems to align with the American Bankers Association data.

Bottom Line

While we still foresee a recession in the near future, we have no reason to believe at this time that it will be a severe one, especially as far as most sectors of commercial real estate are concerned.

Remember: REITs typically have a wider and deeper array of capital sources than virtually any other kind of real estate owner.

- At-the-market equity issuance

- Forward equity offerings

- Privately negotiated operating partnership units

- Unsecured bonds

- Secured mortgages

- Cash-out refinancings

- Term loans

- Credit revolvers

- Preferred stock

- Property dispositions

- Retained cash flow

- Etc.

How many other types of real estate investors have this breadth of access to capital? None.

That’s why we view REITs as the #1 best way to benefit from the eventual recovery in commercial real estate.

Will a near-future recession hurt many REITs? Yes, probably.

But the lower interest rates that a recession would bring with it would more than offset any potential deleterious effects from the recession itself.

That’s why, on the net, when you consider both positive and negative effects, we think a potential oncoming recession would be very good for most REITs. It would turn the REIT bear market into a REIT bull market as investors anticipate lower interest rates and it could result in significant upside potential.

Even blue-chip REITs like Realty Income (O), Alexandria Real Estate (ARE), and Crown Castle (CCI) have crashed and now offer 50%+ upside potential to our estimates of their fair value.

Read the full article here